Extracts from the links appear below. The complete source documents are appended as PDFs to the bottom of the page

British or English Identity?

2006 study of 16 – 21 year olds –

“Britishness does not feature on the list of personal traits which helps define personal identity. This is because young people see (perhaps properly) British identity as a legal construct used only in official circumstances. Additionally, being Welsh, Scottish or Irish has far more emotional resonance than Britishness. Family connections are rated much more significant than a shared British identity. For instance, only a quarter of the 672 young people surveyed said Britishness was more important to them than their family’s country of origin.

In Wales, Scotland and for Catholic participants in Northern Ireland they see the English as arrogant, superior and aggressive. Their opposition to the English means that they are hesitant in accepting a British identity because they think it places them in the same camp as the English. These nations want to be recognised as culturally and attitudinally different from the English. They also want to be seen as distinct and rich cultures in themselves. For Catholic participants in Northern Ireland the political, religious and historical associations that accompany the ‘British’ cannot be overstated.

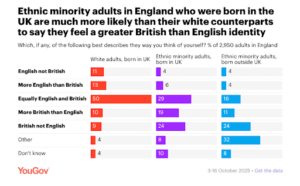

However, young white people in England find it hard to distinguish between being English and British: the two appear interchangeable. The quantitative research also supports this theory highlighting that English young people are far less likely to think their English identity is more important than their British identity, than young Scots or Welsh people.

(This might explain why so few people identified as English in the 2021 census)

(38% among English people compared with 60% in Wales and 85% in Scotland). It begs the questions whether Britishness as a concept is propagated by, and only significant to, the white English population.

Ethnic identities have far more emotional resonance with black and Asian young people. Both black and Asian participants experience a complex layering of national and ethnic identities which become important in different circumstances. There are number of emotional bonds to their parent’s country of origin, and the message for instance, that ‘You are Nigerian” is constantly reinforced as their parents remind them of their heritage and their ‘otherness’ from the white community. This is despite the fact that young people acknowledge that at times they are caught between feeling part of their heritage and not being fully accepted by people in their ‘home country’. Again this is supported by the quantitative evidence with young ethnic minorities far more likely to disagree with the statement ‘Being British is more important to my sense of identity than my family’s country of origin’ (43% compared with 29% among young white people).

2022 – Anecdotal Responses to the Question of Identity

If a non-Black person asks me this loaded question, I’ll usually start with: “I’m from East London/Essex, but I’m Congolese.” But if this comes from a Black person, I’d say: “I’m Congolese but I live in East London/Essex.”

I pretty much said the same thing, but I phrased it differently. Why? Because identity is complex. I was born in Kenya but moved to the UK when I was a few months old and come from a Congolese family. On paper, I’m as British as can be, but I haven’t always felt like that.

Up until the age of around 17, I identified as Congolese because I felt I was. I ate Congolese food, had a good grasp of Congolese culture and history and that was enough. In recent years, though, I’ve started realising how much I don’t know about Congo and that I relate way more to British culture – specifically, Black British culture – than I thought I did.

Habiba Katsha -I lean towards identifying as Black British, but my mother says she’s firmly Congolese.

My aversions to calling myself British lied in the role Britain played in colonisation and slavery. Could I truly be proud of being British knowing what this country has done to Black people? And even today, the treatment of Black people in the UK needs a lot of work.

Though I love being Congolese, I still haven’t been there, can’t fully speak or understand Swahili (my mother’s mother tongue). So yes, I’m Congolese, but today I tend to identify more with the term Black British.

To me, Black British acknowledges that yes, I am British, but I’m also Black. This is my home, but I also have a part of my identity from a different country that is equally as important. My mum on the other hand would still say she’s Congolese, despite her being in this country for more than 26 years.

Aneno-Aciro was born and raised in London, but her roots lie in northern Uganda.

She tells HuffPost UK she feels so close to her culture, it often feels like she grew up over there. “I know my maternal and paternal villages and frequent there a lot,” she says. “There are aspects of my culture that I love, the traditional dancing, the story-telling, the pride that we have, carrying our Nilotic stories on our back that predate all of us. The food, the land, the language and way, way more.”

But during her secondary school years throughout the 2010s, she started to feel confused about her identity. “The zeitgeist [then] was that if you weren’t from Nigeria, Ghana, or Jamaica, your country basically didn’t exist,” she says. “I was told I was too ‘dark’ and [had] several reminders about my appearance that only came from fellow Black people. It left me confused about my identity, and quite frankly, I didn’t feel ‘Black enough.’”

Aneno-Aciro says that this experience was compounded by the area that her family lived in. “If you didn’t grow up in a ‘Black area’, speak the colloquial stuff, your blackness was called into question,” she says. “Fast forward a good few years and I learnt that my experience is just as valid, we’re not a monolith. I feel both Black and British at exactly the same time.”

Iyobosa Idubor-Williams – “When people ask me where I’m from I always say Nigeria first.”

Iyobosa Idubor-Williams, who is a 23-year-old government affairs intern based in Reading, shares that he feels more Nigerian than anything, but relates to the phrase ‘Black in Britain’ – a term people use to describe a feeling of being Black in the UK, but not necessarily a part of British culture.

Idubor-Williams was born in East London but moved back to Lagos between the ages of two and 16. However, he spent term time in a British boarding school before he moved back here permanently. “When people ask me where I’m from, I always say Nigeria first, because that’s what I identify more with and despite the awfully corrupt country that it is, that’s the country that has my heart,” he says.

“During my teens, this identity did slip away having spent my adolescent years in a British boarding school – and being one out of only four Black people in school at one point – I don’t think you can expect anything else.”

2023- Just under half of black Britons are “definitely proud” or “somewhat proud” to be British, according to the largest survey of its kind to date.

(What this study unfortunately was unable to do, was to compare what other Britons feel on the same topic)

The landmark study, which surveyed more than 11,000 black Britons across 16 topics including Britishness, education and the criminal justice system, highlighted the impact of systemic racism in respondents’ sense of belonging and life opportunities.

Campaigners have described the findings as a wake-up call and further evidence of the “chronic level of racial disparities” that black Britons face in the UK.

The research found that the number of black Britons who understand themselves as British (81%) is significantly higher than the number who consider themselves “proud to be British” (49%).

While many black Britons today feel more British than previous generations, the report notes that Englishness was a far more difficult identity to accept. Researchers suggest that for some black Britons, Englishness has become much more strongly tied to whiteness in the wake of Brexit.

(Englishness is tied to being English, which is an ethnic identity, something Guardian writers might not be too happy with)

The Black British Voices research project was launched in 2020 as a collaboration between the University of Cambridge, the Voice newspaper and the I-Cubed consultancy, during the Black Lives Matter protests. As well as the survey, researchers conducted eight focus group sessions and 40 interviews.

The findings show that while the latest census suggests the UK overall faces a “non-religious future” as a decreasing number of people identify as Christian, religion and the church continue to play a particularly important role for black Britons. In the survey, 84% of respondents described themselves as religious or spiritual.

The study also demonstrates a deep distrust of British educational institutions to serve the needs of black British children. The study found that 80% of respondents strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement: do you think racial discrimination is the biggest barrier to young black people’s academic attainment?

The findings show that 95% of participants believe the British national curriculum is failing to teach black history-related subjects, while fewer than 2% of respondents believe that British educational institutions are taking the issue of racial difference seriously.

(Black history is not the history of Britain, which is what is being taught in schools. This is not a complaint we hear voiced by other, larger minorities)

The survey found that 88% of respondents said they experienced racial discrimination in the workplace, while 98% of black Britons indicated they “always” (46%), “often” (38%), or “sometimes” (14%) had to compromise who they were and how they expressed themselves to fit in at work.

(That might also hold true for people of working class, or from different regions of England)

At least 87% of respondents said they did not trust Britain’s criminal justice system. Racial profiling and stop and search laws were the top concerns fuelling the tensions between the police and black communities.

(Black people are over represented in the prison system, but not as much as Muslims. Moreover the prison population of England and Wales contains 0% Hindus. Is that racist?)

Of the young people who participated in the survey, 90% said they expected to experience racial prejudice in the UK as adults. And 93% of young black Britons did not feel supported by the government in relation to the challenges they faced, while 87% did not feel employers and businesses are doing enough to address the employment gap for young. Overall, responses by young Black Britons to questions about their future were 20 times more negative than positive.

Lester Holloway, the editor of the Voice newspaper, said: “This study should be a wake-up call for Britain. We have many fourth-generation Black Brits and, as a community, we should be feeling part of this country. Yet the lived experience of racism in every area of life is leading many to not feel British.

“We cannot keep ignoring racial disparities and its impact. There needs to be a national conversation about this, and we need race back on the political agenda, so we can tackle the causes of this disconnect between Black Brits and the only country they know.”

(Racial disparities also exist within black ethnicities. For example Black African schoolchildren are excluded from schools at a lower rate than their White or Black Caribbean counterparts)

Dr Kenny Monrose, the lead researcher on the project at Cambridge University, said: “We are mindful that historically black communities have been wary of reports conducted on race, as they attempt to limit or invalidate the reality of their lived experiences. However, the carpet of data captured within this report reliably highlights the chronic level of racial disparities and unequal outcomes that they face on a daily basis.”

BRITISHNESS

The number of Black Britons who understand themselves as British (81%) is significantly higher than the number who consider themselves ‘proud to be British’ (49%). Englishness is a more difficult identity than Britishness for many Black Britons. Although a significant majority (81%) of Black Britons understand themselves as British, roughly one in six do not.

BAME

This category is more favourably viewed by a minority respondents (21%) who recognise its historic role in data collection, but who nonetheless see it as dated.75% of respondents overwhelmingly feel this category is reductive and homogenising.Interview data suggest that BAME is perceived as both a sign and symptom of band-aid approaches and thus of failure.

BAME consequently signals both misperception and underestimation of the problems of systemic racism it is intended to address.

EDUCATION

94% of BBVP participants believe Black students suffer from lower educational attainment expectations from educators compared to non Black students. Ten times as many respondents (41%) perceive racial discrimination to ‘definitely’ be the ‘biggest barrier’ to young Black people’s academic attainment as those who think this is ‘definitely not’ the case (4%).

95% of participants perceive the British national curriculum to inadequately accommodate Black history-related subjects. Fewer than 2% of survey respondents believe that British educational institutions are taking the issue of racial difference seriously. The sense that more Black teachers and more focus on Black lives and histories would help is offset by a deep distrust in British educational institutions to serve the needs of Black British children.

(This is almost a desire to self-alienate, the idea that British history should be binned in favour of separate histories for different racial groups.)

THE WORKPLACE

88% of BBVP participants report experiencing racial discrimination in the workplace.98% of respondents indicating they ‘Always’ (46%), ‘Often’ (38%), or ‘Sometimes’ (14%) had ‘to compromise who they are and how they express themselves to fit in at work’.

Black Britons often face protracted and nonlinear career progression, encountering obstacles to promotion and being accused of benefiting from tokenism when they do advance. ‘Fitting in’ is considered to be the major source of discrimination and was ranked by survey respondents higher than unequal pay as the primary workplace obstacle.

Efforts by employers to address racial discrimination at work are often experienced as superficial or even perceived to make matters worse.

YOUNG PEOPLE AND THE FUTURE

90% of the young people who participated in the survey expect to experience racial prejudice in the UK as adults.93% do not feel supported by the Government in relation to the challenges they face, compared to only 3% who do.

87% do not feel employers and businesses are doing enough to address the employment gap for young Black people in contrast to only 5% who do. Responses by young Black Britons to questions about their future were 20 times more negative than positive. 45% of respondents saw Britain as their permanent home, compared to 39% who expressed a desire to live elsewhere.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE

20 years after the MacPherson report, the British criminal justice system – including the courts as well as the police and the penal system – remain highly distrusted by Black Britons.87% of BBVP participants reported that they do not trust Britain’s criminal justice system. Racial profiling along with stop and search laws continue to play an outsized role in fueling tensions between the police and Black communities.

79% of respondents believe that stop and search is used unfairly against Black people.Views on whether the police can be improved by the recruitment of more Black police officers remain deeply divided.

MEDIA AND THE ARTS

Black British perceptions of British media institutions suggest widespread disappointment with what are perceived as entrenched patterns of systematic exclusion. Fewer than 10% of BBVP participants believe theatres and publishing houses are doing enough to encourage Black participation in their sectors.96% of respondents thought Black men and 93% believe Black women are negatively stereotyped in the mainstream media.

90% of survey respondents object to negative stereotyping of Black women and men on TV.61% felt that Black theatre productions were either ‘somewhat’ or ‘definitely not’ embraced by mainstream theatres.

SPORT

Racism within sport is seen to reflect deeply rooted and persistent anti-Black prejudices that should not be tolerated in today’s society but nonetheless are often ignored or even implicitly condoned, and thus allowed to persist.93% of BBVP participants believe British sporting authorities have failed to do enough to combat racism in this sector.

63% of respondents believe that racism in sport has increased in recent years. 95% of respondents felt that social media companies are not doing enough to prevent online racial abuse of Black athletes.

Many respondents shared the view that initiatives aimed at tackling racism in sport are too shallow and superficial, thus trivialising and marginalising a problem that in should be taken much more seriously.

HEALTHCARE

Fewer than 1 in 60 respondents felt they were fairly treated within the healthcare system, which was largely depicted in the BBVP data as a hostile environment. 87% of respondents reported that they expect to receive a substandard level of healthcare because of their race.

Interview data foregrounds the multiple effects of social inequality on health, including not only poverty, unemployment, poor nutrition and inadequate housing but also the stresses caused by everyday forms of racial discrimination.

See also – https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/black-british-voices-report

Over a Third of Black Britons do not see Britain as their permanent Home

Over a third of Black Britons do not see Britain as their permanent home and desire to live elsewhere in the future, according to the findings of a new survey. Polling from the Black British Voices (BBV) project shows even though 45 percent of young respondents said they do see Britain as their permanent home, this was closely followed by 39 percent who expressed a desire to live elsewhere.

For those who have already left the United Kingdom to build a new life ‘back home’ in The Caribbean or Africa, they say the findings suggest a new generation of Black Brits are not going to “stay and suck it up” in Britain anymore.

The idea of returning to Africa is not a new phenomenon. In 1919, Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican Black nationalist and Pan-Africanist, advocated for Black people to physically return to the African continent. He founded the Black Star Line, and purchased two ships to provide transportation for those wanting to return. Almost three decades later in 1948, Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie donated land in Shashamane, to members of the Rastafari movement in Jamaica and other African-Caribbean people wishing to settle in Ethiopia.

ZOE SMITH: ‘A better chance of being treated better’

Speaking to The Voice from Grenada, Zoe Smith, said the pandemic and social media has shifted the mindset of young people who realise they have alternatives. She said: “Rather than feeling like they have to stay in the UK and suck it up, they are more aware that they have options.

“They will use the power of their passport – whether it is a UK passport or a diaspora passport – and choose somewhere where they have a better chance of being treated better.”

Smith said the rise in remote working due to Covid-19 pandemic may also be influencing young people’s future decisions, as they realise “they no longer have to be in an office” but can work anywhere in the world.

Having moved to Grenada in July 2021 because the British education system continuously failed her son, she said more Black families will leave if there is not “massive structural change.” Other findings from the survey paint a bleak picture, with an overwhelming 90 percent of the young respondents saying they expect to experience some sort of racial prejudice during adulthood while living in the UK.

Smith commented: “It would be nice to say the findings make me feel shock or horror, but I’m Black I was born in the UK, so I know fully well what the experience is like.” She added: “The fact that the younger generation know that they don’t have to stay and take it, is perhaps a lesson to the older folks. How long are we going to bang our heads against a brick wall?” Smith said the next Government needs to do more than just “performative” gestures otherwise we will continue to see more young Black people feel disconnected with those who lead the country.

JULIET RYAN

The writer from Watford, started a YouTube series called The Exodus Collective – which shares stories from those in the Black community, who made their ‘Blaxit’ – meaning moving to different parts of the Caribbean and Africa to find a sense of peace.

She said initially she thought the trend was just a “blip” but said three years on, the movement is still growing and is a sign the UK is failing Black families. She added: “When I started in 2020, it was a response to the murder of George Floyd and racism being a main driving factor.

“But in the years that have followed, the cost of living, the insanity that is going on in the Conservative government, there’s so many factors that are making people feel the UK is not the best place to be if you are invested in a sustainable future. “People who are talented, able and ambitious are wanting to go to countries where they can fulfil their dreams rather than go up against an old and complicated system.”

Professor Shawn-Naphtali Sobers, is a professor in Cultural Interdisciplinary Practice at the University of the West of England.

He said the Rastafari community had been championing repatriation for decades. “Rastafari has always talked about the need for repatriation to the motherland, as the safe haven for the global peoples of the Black diaspora. “It is clear that Rastafari had this prophetic vision, which this research shows to clearly be still relevant today, but it has to be said, this is not through the lack of trying, to try and build integrated and peaceful lives in what Rastafari call Babylon. “Evidently, the younger generations still feel the sense of rejection and are essentially proving the Rastafari prophecy to be correct.”

Professor Sobers added many Black British people born in Britain in the 1960s and 70s had a challenging relationship as seeing themselves as British and wanting to permanently live here due to “witnessing the hostility and racism shown to us by the services of the British state, whether that be in education, health, the justice system and all other areas of British society.” He said he is saddened to see feelings of “disconnect” still present in younger generations in 2023.

https://www.ibhm-uk.org/post/is-there-still-a-black-community-in-the-uk